She walked a mile or so to the store at Skyland for a gallon of kerosene.

The shopkeeper filled her can with gasoline by mistake, however.

Her mountain home burned to the ground after the stove exploded.

The boy, whose father years earlier got killed in a dispute over moonshine — not uncommon among folks scratching out lives in the Blue Ridge — suddenly had no family or home.

“What do you think, Elmer?” Milt Emerson asked his wife. “You’d have to cook for another one.”

My grandmother worked most of the day at a wood-fired cookstove to feed her husband, five children, the stable hand and occasionally other workers who helped with the business — taxi cabs, trucking and horses in Luray. They struggled, as did most families in the Great Depression.

But, they had a big garden, a hog for slaughter around Thanksgiving and a cow for milk. Despite the hard times, <a href=”https://www.nps.gov/shen/learn/historyculture/skyland.htm”>George Freeman Pollock</a> created a steady demand for trail horses at his Skyland Resort, several thousand feet above the valley floor. Every spring, my grandfather and his sons rode and led about 30 horses up to the mountain stables. They brought the horses back to town each fall.

The Emersons got to know the mountain folks, including Lawrence F. Buracker, the orphan boy who came to live with them in the mid-1930s.

Lawrence and my father Keith, a few years his junior, shared a second-floor bedroom at the back of the big clapboard house at Mechanic and Hawksbill streets.

Behind in school, Lawrence got tutoring from my aunt Thelma, who taught fourth grade. Despite his academic challenges, Lawrence did well at Luray High School, making friends and the football team.

But, life got tougher.

Milt Emerson died of heart failure on June 7, 1940. Most of the loans he made to people who couldn’t borrow from a bank went unpaid. War came and the business faded.

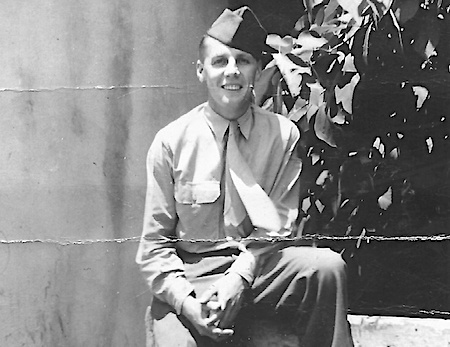

James, the oldest son, enlisted in the Army Air Corps. Lawrence signed up and served with the Army’s 41st Tank Battalion, 11th Armored Division. A month after his 18th birthday, my father followed suit and served with Patton’s Third Army in the slog across Europe.

James and Keith made it home.

Just seven weeks before the Nazis surrendered, Lawrence got killed March 3, 1945, near Mayen, Germany. He lies in the American cemetery at Hamm, Luxembourg.

My grandmother received a telegram and later a $10,000 life insurance check from the Army that helped her family survive. My father learned of his adopted brother’s death only after returning to Luray.

He and other veterans came back to a changed nation, got new jobs, married, bought houses and started families.

My parents built a modest home atop that former garden, behind the clapboard house, on a new street as Luray began to develop. My father started a 39-year career at Shenandoah National Park, ultimately with responsibility for every building from Front Royal to Swift Run Gap, including those Skyland stables where he played as a child and made an important friendship.

Eleven years after the war, I came along and got a name with meaning that took decades for me to appreciate, from a man I never met.

I can only wonder how my life would have changed had I been born a small-town Virginia kid in the 1920s . . . or five years earlier in the 1950s . . . or in the 1840s.

As I walk the farm road each morning, I often think of The Battle of the Bulge . . . Tet . . . Gettysburg.

Would I have had the courage they exhibited?

Lawrence Emerson ~ Warrenton, Va.

Be the first to comment