By Dylan Cooper, columnist

When we can’t think of something in common to talk about in conversation, we usually fall back to the topic of the weather. It seems anyone can be a weatherman these days, especially when the forecast models can be so different from what is actually experienced. Weather is the day-to-day or “short-term” changes in patterns of precipitation, temperature, and other metrics affecting the environment around us. Climate is the “long-term” average of weather, where we look at a record of 10, 20, 30 or more years to find trends and averages over an area.

Local climate data is hard to find for Luray, but I did find an 80-year record that we will take a look at. For the year 2020, the average mean temperature was 55.5 degrees Fehrenheit, which tied for 14th on the list of 80 years. Three of the top ten warmest years in Luray have occurred since 2012. The warmest year on record was actually 1953-1954 at 56.7 degrees F. The precipitation report for last year was 51.6 inches, which was the fifth wettest year on the list of 80.

As we all know, weather varies a lot locally. Taking a step back to the state level gives us a slightly wider glance at climate data. Virginia had its third wettest year on record in 2020, which was only beaten by years 2018 and 2003 in the 125 year record. We had a whopping 18 inches of rain more than the 100 year average of 43 inches. The state also experienced its second hottest year over the same duration of record. Last year tied with 2019 and was beaten only by 2012 for the highest average temperature statewide. The average temperature in VA in 2020 was 57.5 degrees F which equates to 2.8 degrees over the 100 year average.

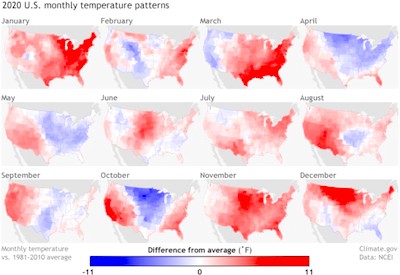

Stepping back further, we can look at the United States as a whole for our 2020 climate data analysis. A preliminary report from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information stated the average temperature for the United States last year was 54.4 degrees F, which is 2.4 degrees above the 20th century average. This was the fifth highest in the 126 year record. All of the top five hottest years have occurred since 2012. Warm daily temperature records were set at a ratio of 2:1 compared to cold temperature records.

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season was also one for the record books. A record high of 30 named storms occurred in the Atlantic basin, with 13 becoming hurricanes (second most ever), and six were major hurricanes. Twelve of these made landfall on the continental U.S. As you may remember, we were well into the greek alphabet and that was only the second time in history that the greek alphabet had to be used since the 21 names were used up. This was the fifth above-average hurricane season in a row, and it marks 18 of the last 26 being above average.

The U.S. sea level records were announced last July and for the prior year, the record was set for the nationwide median Relative Sea Level (RSL) which was a 0.34 meter rise since the year 1920. On the East Coast and Gulf Coast, 57 of the 62 tide gauges broke their RSL records last year. High Tide Flooding (HTF), also called “sunny-day flooding”, had tied for third place on record with a national average of four days of occurrence last year. This is now occurring twice as often as it did in 2000. There were 19 locations where HTF was at a record high with most of those occurring in the Chesapeake Bay area and in the Southeast. HTF is increasing at a linear rate at 19 of 68 tide gauges on the East and Gulf Coasts and at a faster rate at 48 of 68 locations.

Finally, we shall look at the 2020 data for the entire planet. NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies just published their data for 2020 global temperatures. The year 2020 tied 2016 for the hottest year on record globally. The average global temperature was 1.84 degrees F above the 1951-1980 baseline average.

Even though the year made a record, there were a few reasons why 2020 global temperatures were affected by abnormal circumstances. The Australian bushfires at the end of 2019 and beginning of 2020, which burned 46 million acres, were expected to send enough particles into the atmosphere to cool the ground temperatures in that region and even other parts of the globe for months. An adverse effect also occurred when the air-borne particles reached over 18 miles high, into the stratosphere, and that can actually cause a warming of the air around those particles. This was the third extreme wildfire event seen on the planet in three years, a frequency that is expected to continue increasing.

A potential reason for warmer temperatures in certain cities in 2020 was the COVID-19 pandemic keeping pollution-producing human activities at a minimum. Remember back during the lockdown seeing those pictures of metropolises without the usual cloud of smog around them? Typically, those smog particles would have reflected more sunlight back away from the Earth’s surface. Instead, for that part of the year while the air was clear, the small increase in sun exposure to the ground likely led to a small increase in temperature in those areas.

There are a load of other scientific data and reasonings for the record-breaking events we are witnessing with our climate that I cannot possibly include in one column, but perhaps I can continue the research in future columns. My hope with this piece is that I have given you enough of a start on the data, as well as some web links for you to explore, so you can have the evidence to match your own observations of what is happening in the environment around you.

Dylan Cooper is a Page County native and graduate of Luray High School and Virginia Tech. He is a stream restoration specialist for a local non-profit and a registered professional engineer in the state of Virginia. Avid outdoorsman and ardent environmentalist, he resides in Luray with his wife and dogs.

Email: ecoengineer@vt.edu

•••

RELATED ARTICLES

Nature Notebook: Hunting season and CWD

Nature Notebook: Happy New Water Year!

Valley Conservation Council celebrates 30 years of land conservation

Forest Service seeks members for Resource Advisory Committee

Tourism marketing grant to promote Luray, Page as outdoor destination

Senate passes Restore Our Parks Act, bringing $1.1 billion to Virginia

Be the first to comment